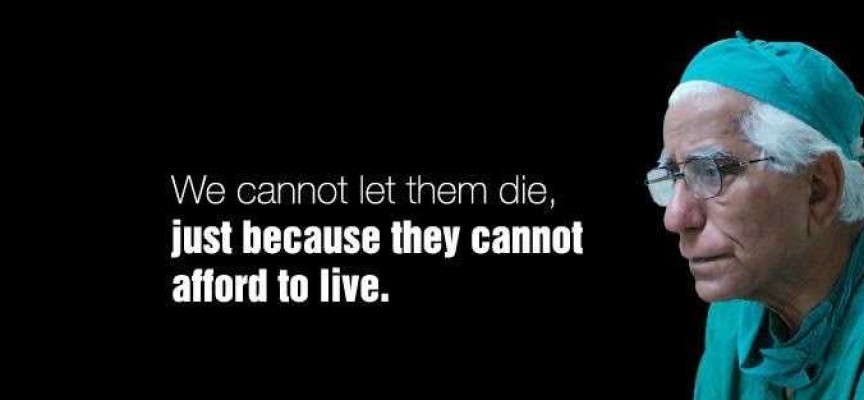

The people who most need medical attention in Pakistan are usually those who can’t afford to seek it. Kidney related diseases and urinary tract infections are the result of contaminated water and unsanitary living conditions, which means that the poor strata of society are most commonly affected. In stark contrast, the treatments are very expensive and require high-tech facilities and expert handling. The life-long dialysis treatments for one person can cost around 160,000 PKR annually, and a kidney transplant requires money in the ballpark of 300,000 PKR. And in case neither is provided, death is the certain outcome.

Syed Adibul Hasan Rizvi is the driving force behind the Sindh Institute of Urology and Transplantation (SIUT). With state-of-the-art facilities and a team of well-educated, experienced and dedicated medical practitioners, the institute provides all urological treatments completely free of cost. Everything from diagnosis to dialysis, medication to supplies, and organ transplants to the continuing post-transplant checkups are taken care of by the hospital. These treatments are considered a general right in this facility, and provided to everyone regardless of their financial status, ethnicity, religion or creed.

Sindh Institute of Urology and Transplantation is therefore one of the most reputed medical institutions in South Asia, both for its charitable spirit and remarkable work. Dr. Rizvi is the recipient of the prestigious Ramon Magsaysay Award for his great philanthropic services providing specialized care to the marginalized segments of society.

Dr. Rizvi was born on the 11th of September, 1938, in Kalanpur, a village 10 km away from Jaunpur in British India. He opened his eyes in the household of a Muslim landowning family of moderate means, as the youngest of nine, having five brothers and three sisters. His father was a self-made man who had worked his way up to become the chief engineer in Juanpur. Dr. Rizvi’s house was named Rahat Manzil – the place of peace. It had a barn for animals and the family grew wheat, barley, sugarcane, and potatoes on their land.

The spirit of philanthropy and the feeling of compassion were instilled in Dr. Rizvi from a very young age. He learned nondiscrimination from his father, who treated the domestic workers as well as he could. The peasants tilling the landowner’s land also lived with them in their house, and Dr. Rizvi grew up watching his father treat the workers’ children as well his he did his own. When it came to third-person observation, he claims that it was “difficult to differentiate between us and the children of the servants.”

From a very young age, Dr. Rizvi wanted to become an engineer as that was the career path chosen for him by his loved ones. But when one of his elder brothers, chosen to be a doctor, suddenly died by drowning, he decided to honor his mother’s wishes and abandoned his engineering plans in favor of medicine.

“When I chose to become a doctor, the closest I could get to engineering was surgery,” Dr. Rizvi explains. “So, from the word go, I had no doubt that I was going to become a surgeon.” And surgery is exactly what he did, after his specialization in urology.

Dr. Rizvi studied medicine at Dow Medical College in Karachi and graduated in 1961. After obtaining his degree, he proceeded to the United Kingdom to further his experience and education. This endeavor took him a total of nine years, and what he learned while abroad proved invaluable later on when he set out to achieve great things.

Dr. Rizvi was introduced to Urology as a specialty by Dr. Poole-Wilson, who he met during the course of a job interview. When asked about his future plans, Dr. Rizvi spoke about returning to his homeland after obtaining his fellowship in surgery since doctors were much needed back home. Dr. Poole-Wilson was surprised at this response, as most people who came abroad saw it as a golden ticket to the good life and soon settled there due to the myriad of opportunities. Dr. Rizvi, however, thought there were many to cater to the public of Britain, but it was Pakistan that could use the expertise. This spirit greatly impressed the interviewer, who would soon become his mentor.

The National Health Service in Britain was what really inspired Dr. Rizvi and led him towards setting up the Sindh Institute of Urology and Transplantation and he hoped to emulate the practice by opening a similar facility in Pakistan which provided high quality specialized medical care. This was aimed towards alleviating the suffering of the poor who could not afford the expensive treatments, as it would be provided completely free of charge.

In 1985, he performed Civil Hospital’s first kidney transplant operation. What had begun as an 8 bed operation in the burns ward soon grew into a separate department, and in 1992, became an autonomous institute within Civil Hospital, now known as the Sindh Institute of Urology and Transplantation.

At first, Dr. Rizvi was met with some opposition. His stance of providing the same treatment no matter what the patient’s social status was supported, but the means of achieving this were not. “I remember many arguing with me that I should screen patients if they could afford to pay and that they should be asked to pay at least a portion of the treatment,” Dr. Rizvi recalls. He was completely against this method, however, and decided questioning a person while he awaited medical attention was an injustice he would not commit or tolerate.

Twenty million people of our population, many of whom belong to Sindh, suffer from diseases that affect the kidneys and other parts of the urinary system. Three thousand people in Pakistan, of all age groups, experience a kidney failure in this country on average each year. With the cost of dialysis four times the per capita income, not many in Pakistan can afford to survive a renal failure in the private sector. This is where the Sindh Institute of Urology and Transplantation comes in; the philosophy behind its inception is that no one should die because they can’t afford to live.

60 to 70 percent of the patients that visit SIUT belong to the rural parts of Sindh, while 17 to 23 percent reside in the urban regions. The rest of the patients come from all over Pakistan. It receives seventy five thousand people each year. These are catered to by five hundred staff members, sixty-five medical residents, and sixteen consultants, who form the dedicated medical team keeping SIUT up and running.

SIUT does not compromise on the quality of treatment just because it is provided free of charge. It uses all state of the art facilities, such as ultrasound scanning and renal angiography, and performs percutaneous renal surgery, lithotripsy, organ transplantation and dialysis. So far it has performed more than 3,600 kidney transplants. In 2003, Dr Rizvi led a team of surgeons that performed the first successful liver transplant on an infant in Pakistan. Dr Rizvi heads the Transplant Society of Pakistan.

The institute’s Dewan Farooq Medical Center, is a six-story addition that houses operation theaters, a pathology laboratory, 350 beds, three intensive care units, three conference rooms, a helipad for emergencies, a training center, nursing and technological schools, four clinical laboratories, rehabilitation facilities, a drug store, a four hundred people auditorium, wards for specialized treatments of different dialysis patients, and a children’s clinic

Assalamvalaykum i feel proud that am a relative of syed abedul hasan rizvi.allah unhay lambi jindagi day.we all love you chachajan.

very nice info given.. perfect!

Such people are true Pakistani. God bless him

Wow! Amazing man

Great man great work. Salute to all of them.

Good Job, I know about him, he is an angel on earth.

Thank you for this article! God bless you.

A fine article, Adeeb Rizvi and his team are doing great job. He is a messiah for the poor. I met several patients in a week . Believe me that they do not own even 100 rupees. SIUT is a great hope for the nephrology patient across the country. Thanks for the article,

Suhail Yusuf

Science Journalist and visiting fellow, Duke University NC