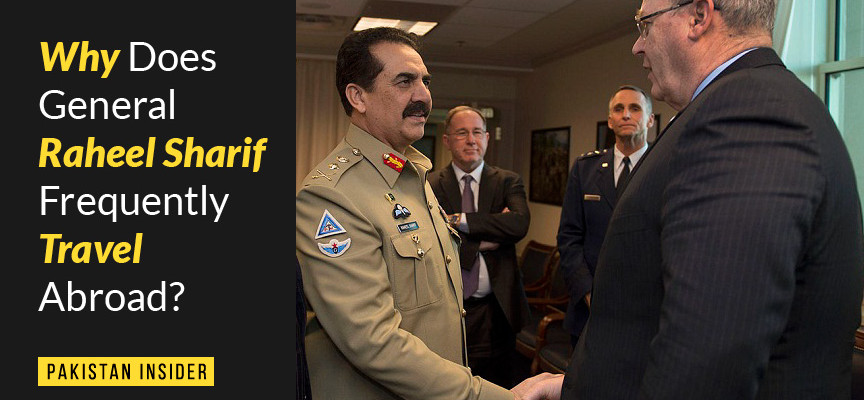

General Raheel Sharif, Pakistan’s 15th army chief, is currently on an official five-day visit to the US. This comes almost a month after his visit to Turkey. Many negative assertions have been by world media on his recent visit. Some said he wanted to “embarrass” Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif’s recent US visit whereas the Indian media, as expected, mounted another cheap attack by claiming that General Raheel “invited himself”.

Although it is true that General Raheel was not formally invited, such unexpected high-level meetings are common among the global military and intelligence circles. For example, the routine visits by ISAF-NATO commanders or CENTCOM chiefs to Rawalpindi are mostly of the guests’ own volitions; the agenda on such meetings is to apprise the Pakistani military leadership about current assessments and future concerns developing among allied countries fighting the so-called War on Terror. Similarly, after the heart-wrenching APS Peshawar attacks of December 2014, General Raheel and DG ISI Lt Gen Rizwan Akhtar went to Kabul without any invitation. The issue of “invited / not invited” is of no concern in such huddles.

Such flash meetings highlight their significance and urgency. They are only held when national interests are to be secured before it’s too late. Some of the other countries General Raheel has visited as Chief Of Army Staff (COAS) include Italy, South Africa, Russia, China, Saudi Arabia, Turkey and the UK. If you observe the names closely, these are countries which are direct and influential stakeholders in the post 9/11 security milieu. The US holds primary importance for Pakistan because the latter was compelled into becoming a “frontline ally” by it, as it planned to invade Afghanistan and create disorder in the regional security balance. Washington is viewed as both an ally and troublemaker by Pakistan but then again, the same can be applied to how the former views Islamabad.

Not precisely.

History has shown that Washington has always assumed Pakistan to have two capital cities: Rawalpindi (military) and Islamabad (civil). Not that the Pentagon is in Washington and hence we can’t say the same for the US; the fact is that in its history mired in confusion and chaos, Pakistan has suffered persistent periods of military dictatorship. Elected representatives and the armed forces have not gone along well in the past leading to growing levels of distrust and occasional public friction.

The first time a Pakistani civilian government completed its term in office (5 years) was between late 2007 and early 2013 with Mr Asif Ali Zardari as President and Misters Yousaf Raza Gilani and later Raja Pervez Ashraf as Prime Ministers. The credit goes to previous army chief General (Retd) Ashfaq Parvez Kayani who reined in the military from repeating past mistakes despite the abundant opportunities it had courtesy of the government’s incompetence and wrongdoings. Thus, the military set a precedent for non-intervention in public governments. During the PPP regime, the government had Ms Hina Rabbani Khar as a robust Foreign Minister who effectively projected Pakistan’s regional and global foreign policy aspirations. Misters Naveed Qamar and Ahmad Mukhtar, the two Defence Ministers during this period, both proved to be ineffective and visibly undeserving of their designations. With near zero knowledge of national defence issues, almost their entire routine dependency was on subordinate bureaucrats who had their own financial and political interests to secure.

When Mr Muhammad Nawaz Sharif assumed charge as Prime Minister of Pakistan for the third time, he was mindful of bitter past experiences with late President Ghulam Ishaq Khan (former bureaucrat) and former COAS General (Retd) Pervez Musharraf. This is why the first thing he did when selecting Kayani’s successor was to supersede the Generals who were apparently part and parcel of the process whereby the Sharifs were ousted to Saudi Arabia (Lt Gen Haroon Aslam et al). The appointment of Khawaja Muhammad Asif as Defence Minister was nothing short of stupid. First, because the gentleman has a documented history of lashing out against the military. Second, he too has near zero knowledge of defence and military matters. Third, he’s already holding another busy portfolio as Minister of Water and Power, struggling to cope up with the challenges facing Pakistan’s critical power generation requirements.

The truth is, although these two pillars of the state (executive and armed forces) have lowered chances of snubbing each other, it will still take many years of perhaps a decade or two before they trust each other. Which brings us to a critical issue:

Does the Pakistan Army not trust its own government?

I believe the army has issues trusting the government’s capabilities and competencies, not their sincerity. As mentioned earlier, the absence of a Defence Minister who can effectively relay the military’s concerns in part justifies General Raheel’s frequent trips abroad. On the other hand, it is very much part of a service chief’s mandate to visit regional and global partners to discuss current issues of mutual concern which could have far reaching consequences for their country’s national security. It is also a fact that Musharraf as a serving COAS had made open / covert agreements with the US military.

Since 9/11, George W Bush and presently Barack Obama have steered the US administration as Presidents in this self-initiated war. The Department of Defence (Pentagon), State Department, Congress and Intelligence Community (CIA, NSA, etc) have worked in tandem, persistently and thoroughly, toward the realization of America’s ambitions in our troubled part of the world. On the other hand, The first 6 to 7 years of engagement with the US government was by one man alone, then COAS General Musharraf or, in general terms, Pakistan Army as an institution. It was only from late 2007 onward that the civilian administration was given some ‘burden’ by the GHQ to share.

Thus, the previous inexperience and still least significant improvement of the civilian administration in handling bilateral defence ties with the US cannot and should not be left alone. In the short term, many will certainly continue to perceive it as a domineering signal to the Prime Minister’s Office. Ultimately, this too will prove to be in Pakistan’s best interests.

The actual question most people never seemed to ask was, why didn’t DG ISI meet with his CIA counterpart John Brennan? This also helps us to understand the business with which COAS General Raheel Sharif called upon the CIA Director in Langley. A service chief meeting a foreign spy chief can only be linked to the ongoing efforts for effective peace. Intelligence chiefs can only discuss their interests / concerns but it is ultimately land, air and naval forces which take decisive action based on well-developed counter-terrorism plans. The ISI is answerable and subordinate to the Prime Minister’s Office but in technical and operational issues, especially in war, it receives final instructions from GHQ.

If readers remember, the ISI and Afghanistan’s NDS had come to an intelligence-sharing agreement which was soon dogged down and effectively ‘ripped apart’ by the Indian RAW. A spate of anti-ISI statements by NDS spokespeople has followed since them confirming India’s success in sabotaging efforts for meaningful Kabul-Islamabad cooperation; or Kabul-Rawalpindi ties, to be precise. Foregoing in view, General Raheel Sharif’s meeting with the CIA Director are apparently an effort to take a crucial intelligence stakeholder in Afghanistan on board so it can pressurize Kabul to stop its rhetoric and sit on the negotiating table. In this way, it is hoped that India’s belligerence in war-torn Afghanistan will be minimized, if not entirely halted.

Finally, another crucial aspect of General Raheel’s meeting is to discuss the wider regional security developments in the Middle East, Central and South Asia. Pakistan’s executive leadership in Islamabad was visibly confused on several critical issues such as the requests by GCC to join a war on Yemen (which Islamabad wanted to readily accept but Rawalpindi considered it against national interests), or the labeling of Gwadar and Chabahar as “sister ports” by the Prime Minister himself in a meeting with Iran’s National Security Adviser. These are issues which Islamabad does not seem to properly understand. On the contrary, Islamabad has outdone itself in expanding ties with the landlocked Central Asian Republics (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan), India and China. One would wonder what magic wand Prime Minister Sharif and his subordinates use in relations with such countries. The answer is simple: “Business”.

The most realistic assessment of the present civilian government in Islamabad is that its policies are oriented toward economic and infrastructural development which ultimately means big business triumphs and lost lasting relations with partners even after official tenures. Credit must be given where due and they certainly seem to have pulled up the right strings in this regard. Back to square one, Pakistan is left with the dilemma of having poor representation in the global defence and security sphere. This is where General Raheel Sharif fulfills his responsibilities.

No comments!

There are no comments yet, but you can be first to comment this article.